Natural language models: GPT-2 causal text generator

November 30, 2025

This week, we will be using a decoder to generate movie reviews. First, I will walk through the fine-tuning process. Then, I will show how well the decoder autocompletes movie reviews. As a note, the fine-tuning process is almost identical to fine-tuning an encoder, so there will be a lot of similarities between this and the previous post.

The foundation to text generation is masked self-attention and autoregressive training. Let’s assume we have a sequence of tokens $T_1, T_2, \ldots, T_n$. Self-attention lets token $T_i$ see all tokens in the sequence $\sum_{k=1}^{n} T_k$. This is bidirectional self-attention (unmasked), which we discussed last post. For causal language models, this won’t work since we can only use the past tokens to predict the next. This is where masked self-attention comes into play. With masked self-attention, the learning is unidirectional (left-to-right), which means that token $T_i$ can also see all tokens in the sequence $\sum_{k=1}^{i} T_k$. The reason for using the word ‘‘masked’’ is that a mask is applied to the attention matrix to mask all future tokens converting the matrix into a lower triangular matrix. Autoregressive training is a training objective where the model predicts token $T_i$ using all previous tokens $T_1, T_2, \ldots, T_{i-1}$ by minimizing a log-likelihood objective function. These two concepts allow the model to learn sequential dependencies and apply this to text generation [1,2,3].

The model we will be fine-tuning it GPT-2 (Generative Pretrained Transformer 2). This is a transformer-based neural network that has been trained on a massive amount of text found on the internet. This model is used to generate the next word in a sequence in a coherent and contextual way. As previously mentioned, the original model was developed by OpenAI in 2019 and a smaller version (~124M parameters) was made available on the Hugging Face website [4], which is the one we will be using. Our job is to fine-tune it to the specific problem we are considering, which is to generate movie reviews based on sentiment. We are not generating sentiment, but outputting a continuation of an input text that contains some form of sentiment.

The first step is defining our parameters. Like previously seen, our parameters will be saved in a .yaml file and we will use SimpleNamespace as an easy way to store and access these parameters. Here are the parameters we will be using:

{

"model_name": "gpt2",

"dataset": "imdb",

"seed": 42,

"dpi": 400,

"max_token_length": 128,

"train_size": 3000,

"val_size": 500,

"lr": 2e-05,

"warmup_ratio": 0.1,

"epochs": 3,

"train_batch_size": 4,

"eval_batch_size": 4,

"strategy": "epoch",

"fig_path": "../outputs/",

"res_path": "../results/"

}

From here, we load the dataset, model, and tokenizer. This is done as follows:

dataset = load_dataset(cfg.dataset)

inst = CausalTextGeneration(cfg.model_name)

dataset = inst.clean_data(dataset)

data_tokenized = inst.tokenize_dataset(dataset, cfg.max_token_length)

data_collator = inst.data_collator()

We have wrapped all the necessary code in the CausalTextGeneration custom class. In this class, we can find methods to import the dataset, clean the dataset, initialize the model, tokenize the dataset, etc. This class is defined as follows (I will omit the docstrings and unused methods for brevity. See the file model.py for more information):

class CausalTextGeneration():

def __init__(

self,

model_name: str

):

self.model_name = model_name

self.device = get_device()

self.tokenizer: PreTrainedTokenizerBase = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(model_name)

self.tokenizer.pad_token = self.tokenizer.eos_token

def clean_data(

self,

dataset: Union[Dataset, DatasetDict],

cutoff: int = 2000

) -> Union[Dataset, DatasetDict]:

dataset = dataset.filter(lambda x: len(x["text"].strip()) > 0)

dataset = dataset.filter(lambda x: len(x["text"]) < cutoff)

return dataset

def tokenize_text(

self,

prompt: str,

padding: Union[bool, str] = True,

truncation: Union[bool, str] = True

) -> dict[str, tc.Tensor]:

inputs = self.tokenizer(

prompt,

padding=padding,

truncation=truncation,

return_tensors="pt"

)

return to_device(inputs, self.device)

def tokenize_dataset(

self,

dataset: Union[Dataset, DatasetDict],

max_token_length: int

) -> Union[Dataset, DatasetDict]:

def tokenize_fn(batch):

tokenized = self.tokenizer(

batch["text"],

padding=False,

truncation=True,

max_length=max_token_length

)

return tokenized

data_tokenized = dataset.map(

tokenize_fn,

batched=True,

remove_columns=["text", "label"],

)

return data_tokenized

def data_collator(

self,

mlm: bool = False

) -> DataCollatorForLanguageModeling:

data_collator = DataCollatorForLanguageModeling(

tokenizer=self.tokenizer,

mlm=mlm

)

return data_collator

def load_model(

self,

) -> PreTrainedModel:

model = AutoModelForCausalLM.from_pretrained(

self.model_name,

).to(self.device)

model.config.pad_token_id = self.tokenizer.pad_token_id

return model

def evaluate_model(

self,

prompt: Union[list[str], str],

model: PreTrainedModel,

max_new_tokens: int = 25,

do_sample: bool = True,

top_k: int = 25,

top_p: float = 0.95,

temperature: float = 0.7,

repetition_penalty: Union[int, float] = 1.1

) -> Union[tc.Tensor, GenerateOutput]:

inputs = self.tokenize_text(prompt)

model.eval()

with tc.no_grad():

outputs = model.generate(

**inputs,

max_new_tokens=max_new_tokens,

do_sample=do_sample,

top_k=top_k,

top_p=top_p,

temperature=temperature,

repetition_penalty=repetition_penalty,

pad_token_id=self.tokenizer.pad_token_id

)

return outputs

I will omit the explanation of each method since most of these were explained in the previous post, but I will go over key differences. For decoders, we will use the Hugging Face class AutoModelForCausalLM since we are now dealing with a causal model, which means that the model depends on the previous information to generate the next word. This is the key difference between encoders and decoders. The next key difference is found in the method tokenize_dataset. We had previously made the default for padding True, but for decoders we make it False. The reason has to do with the length of the reviews. Since we are setting the max token length to be $128$ (see parameters), no padding will actually occur since this length is less than the total length of a review. Hence the token vector will be fully composed of tokens with no blank space and padding would be useless.

We are also now using a pre-defined data collator initialized in the method data_collator, where we import the Hugging Face class DataCollatorForLanguageModeling. This collator automatically takes care of padding (if needed) and masking (as well as other things) for language models. For a causal languange model in particular, we set mlm=False, which tells the collator that the model should be trying to predict the next token. If true, the collator would follow BERT’s stragety of data preparation. There is actually a Hugging Face class called DataCollatorForCausalLM, which is used primarily for text generation models, but I am working with an older version of the transformers library where it is not yet available.

Another difference is that we have now included an evaluate_model method. As one can infer, it is used to evaluate the model using new, unseen data, but now we have different parameters to consider. Let’s go over each individual parameter in model.generate():

- max_new_tokens = $25$

- This is the total amount of tokens that will be used in the text generation.

- do_sample = True

- Tells model to sample from probability distribution instead of picking the highest-probability token.

- do_sample = False $\rightarrow$ deterministic.

- do_sample = True $\rightarrow$ random sampling.

- top_k = $25$

- Sorts logits, keeps top $25$ most probable tokens, and draws samples from them.

- Lower k $\rightarrow$ more deterministic.

- Higher k $\rightarrow$ more random.

- top_p = $0.95$

- Keeps the smallest set of tokens whose cumulative probability $\ge 0.95$.

- Can be used in conjunction with top_k, which amounts to picking tokens that intersect with these two conditions.

- Helps adapt to uncertainty by keeping the token selection dynamic since it is based on a probability mass as opposed to a fixed number.

- temperature = $0.7$

- Scales softmax distribution before sampling.

- Lower T $\rightarrow$ more deterministic.

- Higher T $\rightarrow$ more random.

- repetition_penalty = $1.1$

- Discourages the same token from reappearing by scaling all logits that have already been used by some value $> 1$.

- This occurs when there is a lack of sampling diversity, which causes reinforcement of certain phrases/tokens.

Now, we look at the TrainingArguments and Trainer classes:

training_args = TrainingArguments(

output_dir=cfg.res_path,

overwrite_output_dir=True,

report_to="none",

eval_strategy=cfg.strategy,

save_strategy=cfg.strategy,

logging_strategy= cfg.strategy,

learning_rate=cfg.lr,

per_device_train_batch_size=cfg.train_batch_size,

per_device_eval_batch_size=cfg.eval_batch_size,

num_train_epochs=cfg.epochs,

warmup_ratio=cfg.warmup_ratio,

seed=cfg.seed

)

The TrainingArguments parameters are mostly the same as for the encoder. One big difference is the parameter warmup_ratio. This parameter controls the learning rate at the start of the training by slowly ramping up the learning rate. It initially starts the learning rate at $0$, then linearly increases it until it reaches the max learning rate (chosen by user) and decays from there. The warmup length is given in steps, which is taken by scaling the total steps by the warmup ratio. The purpose of this parameter is to gradually change the model weights at the start of training since the weights are not yet stable.

The main body of the Trainer is essentially the same as before, expect the last two lines are replaced by the data collator. In this case, we choose to not pass in any metrics since we will be calculating the perplexity of the evaluation loss (explained later). The Trainer looks like the following:

trainer = Trainer(

model=model,

args=training_args,

train_dataset=data_tokenized["train"].shuffle(seed=cfg.seed).select(range(cfg.train_size)),

eval_dataset=data_tokenized["test"].shuffle(seed=cfg.seed).select(range(cfg.val_size)),

data_collator=data_collator

)

As before, we pass in the model, the training arguments, the different datasets, and the collator (new!) into the trainer. These datasets are huge so we shuffe, seed, and select a subset of the train ($3000$ samples) and test ($500$ samples) set as a demonstration. In actual fine-tuning, it’s essential to use all the available data. Now, all we have to do is run trainer.train() and the model begins to train.

For our example, we get the following metrics:

Epoch Training Loss Validation Loss

1 3.870400 3.709818

2 3.685000 3.707382

3 3.607300 3.709974

While the training loss is decreasing, it is not decreasing by much. On the other hand, the validation loss starts to decrease then slightly increases. While this may seem troubling at first glance, it is actually not that bad. GPT-2 is actually a very large model, which means that fine-tuning will only slightly decrease the loss. Not to mention, we are only fine-tuning with $3000$ samples. This is such a small sample size in comparison to the data used to train the model that such a small step size in training loss is to be expected. This also partly explains the increase in validation loss during the last epoch since the sample size for the validation dataset is $500$. The change in loss is in the hundredth decimal place, which for most applications can be attributed to small fluctuations (a.k.a. noise). There is a possibility of slight overfitting, but I don’t think there is enough proof. More tests need to be considered with a larger sample size to determine if the model is indeed overfitting.

We can also calculate the perplexity to determine how well the model learned. Perplexity is a way to measure how well a model can predict the next token [5]. It is calculated as the exponent of the average cross-entropy loss. In other words,

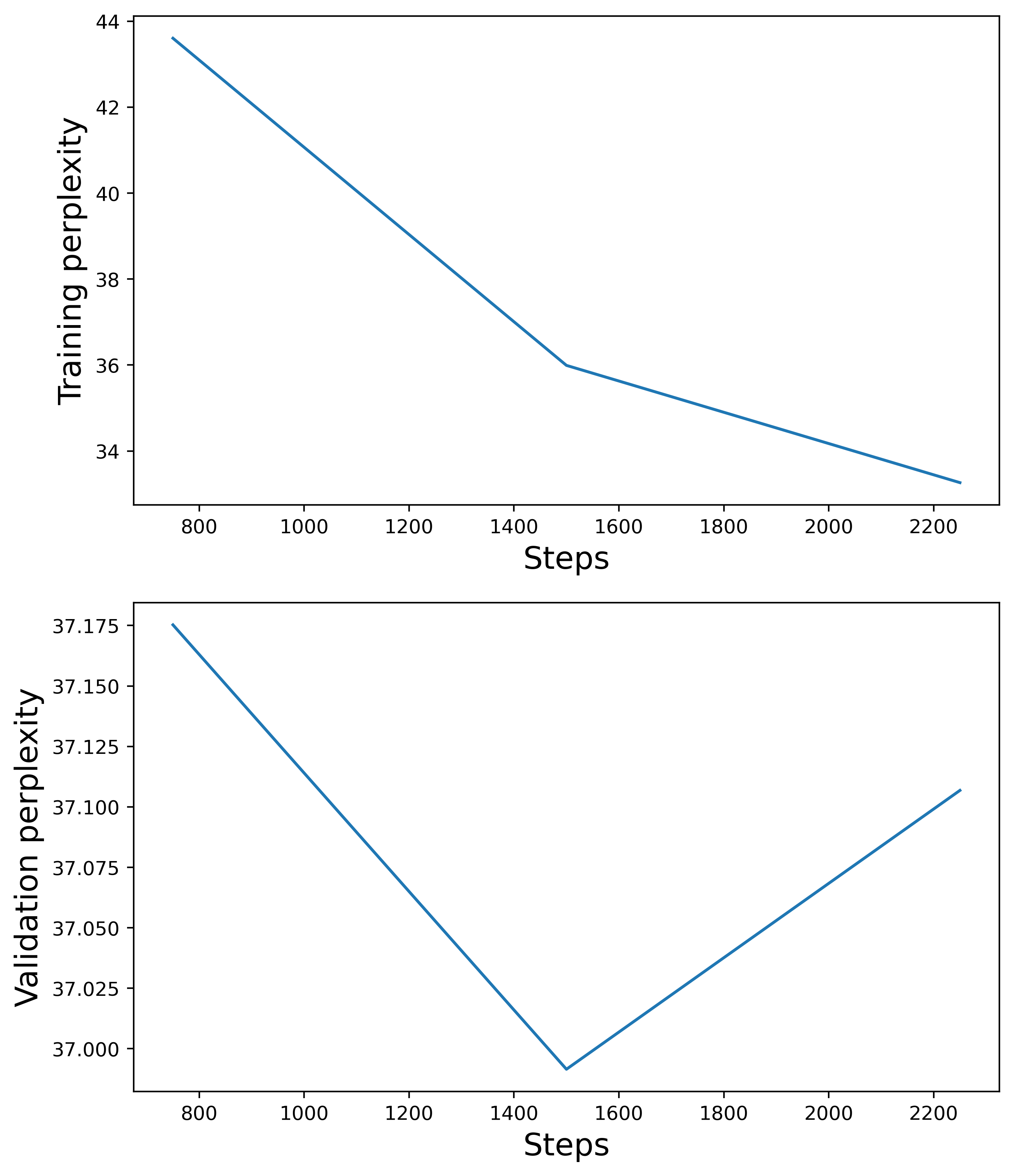

\[\mathrm{perplexity} = e^{\mathrm{loss}}.\]The lower the perplexity, the less token ‘‘choices’’ the model has, hence the more accurate the model prediction. The higher the perplexity, the more token ‘‘choices’’, the more uncertain the model is of its predictions. Ideally, the perplexity has an exponential decay behavior as the model learns. Here is a plot of the perplexity for the training and validation phases:

From the plot, we see that the training perplexity does indeed follow an exponential decay behavior. On the other hand, the validation perplexity increases, which is attributed to what was already mentioned above. Note that steps is the global steps taken during the fine-tuning of the model.

Now that our model is fine-tuned, let’s see how well it can autocomplete movie reviews. Here are beginning of reviews that I created:

reviews = [

"This movie was terrible. The acting was mediocre.",

"I highly recommend this movie to everyone.",

"This was a great movie. I wish it was longer.",

"I do not recommend this movie. The actors are terrible.",

]

In this example, I chose to make the sentiment obvious to see how well the model could understand this and expand on the review. The code that calls the evaluate_model method and prints out the generated text is:

outputs = inst.evaluate_model(reviews, model)

for i, seq in enumerate(outputs):

print(f"Seq. {i + 1}:")

print(f"{inst.tokenizer.decode(seq, skip_special_tokens=True)}")

print("\n")

Here are the outputs of the model:

Seq. 1:

This movie was terrible. The acting was mediocre.It is a very good horror film, but I think it will appeal to many people as well (especially the young ones).

Seq. 2:

I highly recommend this movie to everyone.

If you want a good laugh, go with the story and characters of The Sopranos. If not then read

Seq. 3:

This was a great movie. I wish it was longer. It is not as good as the first one, but this time you can see why people are so angry and upset about what

Seq. 4:

I do not recommend this movie. The actors are terrible. They had an awful time with the acting in it, and I have yet to see a single scene where they did anything other

Overall, the expanded reviews generated by the model seem to somewhat fit the sentiment of the input reviews. There are no issues with Sequence 1 and 4, but we should analyze the other two. Sequence 2 seems to deviate from the inital sentiment. It goes on to talk about The Sopranos even though the input text did not mention anything about that show. Sequence 3 seems to not quite understand what sentiment it is supposed to show, but this is because the sentence ‘‘I wish it was longer.’’ can be interpreted as a negative sentiment even though the first sentence has a positive sentiment. So the output seems to make sense.

Let’s try some harder reviews.

reviews = [

"Wow! I was suprised by how much ",

"This film was such a surprise. ",

"I never thought I would ",

"This movie makes me want to yell "

]

As you can tell, these reviews are more difficult to determine sentiment from. They are ambiguous as to whether they think the movie was good or bad. Let’s see how well the model categorizes them:

Seq. 1:

Wow! I was suprised by how much vernacular this film used to be, and also the way it kept me guessing. For starters: How would you like a

Seq. 2:

This film was such a surprise. A beautiful movie with some great characters, the director and actors had wonderful chemistry to create this story that is very entertaining - even

Seq. 3:

I never thought I would This movie was so bad, but it is. It's not that BAD though! Just an awful story with no redeeming

Seq. 4:

This movie makes me want to yell The Devil is a Bad Idea. It's just terrible, it has no suspense and the plot doesn't move at all!

In this case, the model does a decent job in generating reviews with varying sentiment. This may be because the second batch gave the model more flexibility in producing reviews that kept to one sentiment, as opposed to giving it a sentiment and making it work off that. Sequence 3 and 4 do seem to have fluidity issues, but they still kept a consistent sentiment. Overall, the text generation for both batches were pretty good for the amount of data we used to fine-tune the model.

In general, the model’s performance can be improved by fine-tuning with a larger dataset. I purposely chose to cap the training set at $3000$ samples because my GPU kept running out of memory when running for a larger sample size over $3$ epochs. This can potentially lead to issues since it is known that fine-tuning with small datasets can potentially lead to overfitting or ‘‘catastrophic forgetting’’, which is where the model loses previously learned information [6]. Another way to improve performance is to increase max_token_len. I chose $128$, but ideally, one should choose $256$ or $512$. The reason I had to go with $128$ was also because of my GPU. I did try running the fine-tuning on my CPU with larger sample sizes and/or max token lengths, but it was not feasible due to time constraints. Another test that can be done is training with more epochs to get more steps on the perplexity curves. This could help rule out the model overfitting. Of course, one can also experiment with varying the learning rate, batch size, and warmup ratio, or include weight decay.

As a sidenote, a common way to avoid catastrophic forgetting is using parameter-efficient fine-tuning techniques such as Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) [7]. This technique works by freezing the model weights and fine-tuning with a batch of small low-rank matrices (called LoRA adapter) instead of the full model parameter set, making the fine-tuning process much faster and more memory-efficient. This drastically reduces the number of parameters that need to be trained, as well as keeps the base model unchanged. Afterwards, if one chooses to change the behavior of the model, the LoRA adapter can be swapped out and the base model can once again be fine-tuned with a different LoRA adapter.

In summary, we have learned how to fine-tuned a GPT-2 model to understand how reviews sound (good or bad) and determine what kind of sentence it should generate in continuation. We also learned about perplexity and how it can be used to describe the effectiveness of a model to generate accurate text. Overall, the model performed well on reviews that had pre-defined and obvious sentiment, but did not do so well with ambiguous reviews, which was expected. There is room for increasing the model’s capability of producing better review continuations, as well as making better conclusions on ambiguous inputs.

The code and plot presented in this post can be found on my Github under the gpt-2-gen repo [8]. Feel free to reach out if you have any questions about what we covered this week. I’ll be taking a few weeks off, but will come back with more about building and employing decoders. Stay tuned!

- [1] Dzmitry Bahdanau, Kyunghyun Cho, & Yoshua Bengio, Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate, arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.0473, 2014.

- [2] Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, et al., Attention is All you Need, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2017.

- [3] Yoshua Bengio, Réjean Ducharme, Pascal Vincent, & Christian Jauvin, A Neural Probabilistic Language Model, Journal of Machine Learning Research, 2003.

- [4] Alec Radford, Jeffrey Wu, Rewon Child, et al., Language models are unsupervised multitask learners, OpenAI blog, 2019.

- [5] Rafal Jozefowicz, Oriol Vinyals, Mike Schuster, et al., Exploring the Limits of Language Modeling, arXiv preprint arXiv:1602.02410, 2016.

- [6] Jeremy Howard & Sebastian Ruder, Universal Language Model Fine-tuning for Text Classification, Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2018. DOI: 10.18653/v1/P18-1031.

- [7] Edward J Hu, Yelong Shen, Phillip Wallis, et al., LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models, 2021.

- [8] Alberto J. Garcia, GPT-Style Language Model, 2025. Available at: https://github.com/AJG91/gpt-2-gen.